Welcome to a Thursday evening edition of Progress Report.

If you have a healthier relationship with the internet than I do, it may come as news that Twitter could collapse under the weight of Elon Musk’s ego as soon as tonight. For all the manifold problems that it has caused, Twitter is also a lifeline to the world for millions of people, and at this point, still the fastest way to keep up with news, so it will honestly be a shame to see its demise, should that wind up being its fate.

At the same time, the fact that the app will crash because workers at the company abandoned a brash, phony, malicious billionaire to his own incompetence will make for a poetic ending for the platform that helped to put another brash, phony, malicious billionaire in the White House. Let’s call that progress.

Tonight, we’ve got a deep report on Michigan Democrats’ six year journey from the political wilderness back into full control of state government for the first time in many decades. We trace what happened when they hit their zenith in 2016, when they were fully locked out of power by a dominant Republican Party, to Election Day 2022, which saw a blue wave sweep through the Wolverine State.

It’s an instructive story for other state Democratic Parties, because it doesn’t simply involve spending a ton of big donor money on TV ads. In fact, it’s the complete opposite of that.

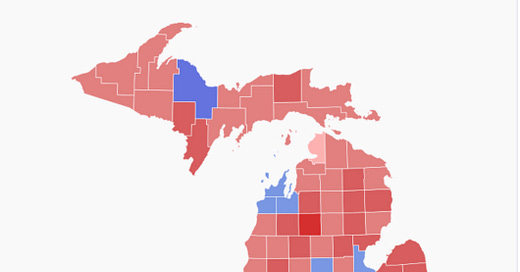

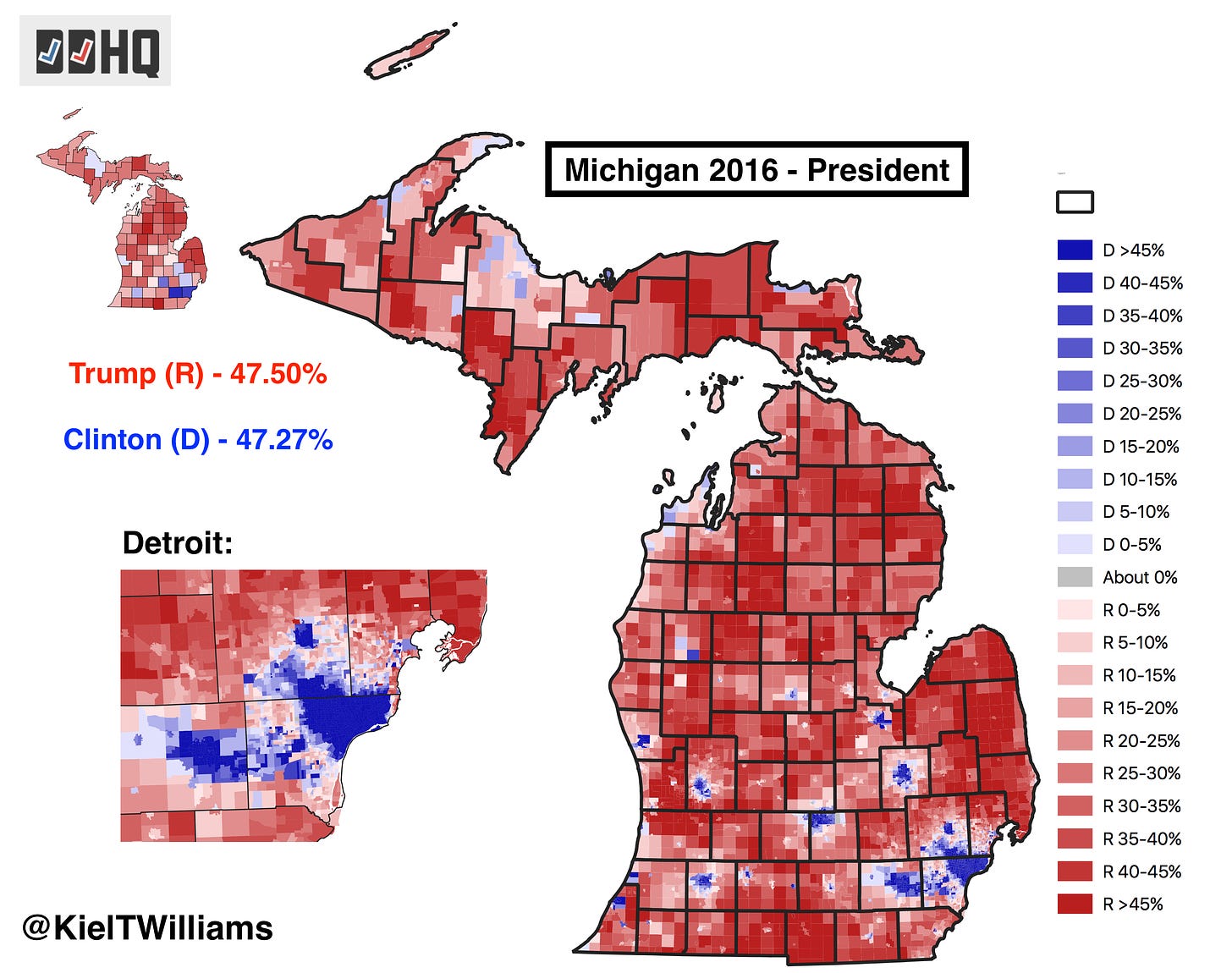

When Donald Trump swept through the Upper Midwest in 2016, it seemed as if he’d finished off a dramatic realignment in the Rust Belt, the longtime blue firewall that was suddenly GOP territory. Democrats found themselves locked out of power and staring at the prospect of permanent minority status across the region, with structural odds stacked against them.

The loss of Michigan was particularly stunning — the spiritual home of the American labor movement, now controlled by a Republican state government trifecta and red on the electoral college map for the first time since 1988. With a gerrymandered hold on the legislature, a two-term governor, and a bottomless pit of money from the far-right DeVos family at their fingertips, Republicans looked to have the state locked down.

Now, just three cycles later, Democrats have seized full control of Michigan once again, with their own state government trifecta, a large majority on the state Supreme Court, control of key county commissions, and a majority of the state’s Congressional districts

How did this massive shift happen in such a relatively short period of time? Zoom in on last week’s triumphs and there are a number of relatively clear factors.

Candidate quality is at the top of that list. Popular Democratic incumbents faced off against Republican nominees that “wouldn’t have been elected dog catcher in any other year,” as one Michigan political insider puts it. Right-wing extremists were also forced to run in districts that were no longer explicitly designed to protect them. And with abortion rights quite literally on the ballot, there was no risk of depressed turnout.

None of those factors were flukes or happy accidents. It took more than five years of careful planning on the part of both party, outside allies, and activists.

Nowhere to Go But Up

Trump’s shock victory in 2016 left Democrats bewildered and reeling, the first steps in the stages of electoral grief unique to the party’s most engaged members.

“They only lost by 10,000 votes, it was an extremely close election,” says Susan Demas, editor-in-chief of the Michigan Advance, “but whenever Democrats lose, they lose their minds, and there's a lot of bloodletting and [questioning] ‘what did we do wrong?’ Which can be healthy, and it can also put people into a spiral. But alongside Trump, there were signs that things weren’t all roses for the Democratic Party.”

The problem was obvious enough: Michigan’s post-industrial white working class voting base, which had been turning red already, finally jumped ship for Trump, who made opposition to free trade deals that allowed automakers to ship manufacturing overseas a key part of his campaign. Blue collar Macomb County was one of 12 counties that Trump flipped that year, while the longtime Republican residents of Michigan’s wealthy suburban counties wound up holding their noses and voting for him, too.

Save for the liberal enclave in the southeast corner of the state and a few other isolated counties sprinkled here and there, the Michigan mitten was almost entirely red. In hindsight, it wasn’t all that shocking — Barack Obama cruised in Michigan in both 2008 and 2012, but as one Democratic county chair tells Progress Report, his campaign hadn’t left any long-term infrastructure in the state. When the 2016 election rolled around, they were caught short-handed, as were some of the unions that traditionally help them out.

“It was clear that in order for Democrats to retake the governor's mansion and the other statewide elected offices in 2018, there needed to be a much more coordinated effort to do grassroots organizing,” says Rep. Mari Manoogian, who was elected to her first term in that cycle. “We didn't change party leadership in between those two elections, but we just continued to do more grassroots organizing.”

Terms like “grassroots organizing” have been co-opted into the messaging style guides of eager partisans looking to raise money, but in this case, it was warranted. The state party, underfunded and ignored by the Clinton campaign, struck out on its own to retake some of the real estate that Trump had seized.

The first step was the launch in early 2017 of Project 83, which aimed to put full-time organizers in each of Michigan’s 83 counties. It required budget cuts, innovative fundraisers, and checks written by Sen. Debbie Stabenow, who was up for re-election in 2018, but they ultimately made it happen, strengthening more active local parties and rebuilding a presence in counties that Democrats had long since written off. They would be out in the field

Stabenow was “someone who pushed early for making sure we had physical grassroots organizing, and not just email and texting,” Manoogian recalls.

The Senator was also a major booster of reviving One Michigan, which oversaw the coordinated campaign for Democratic nominees after the 2018 primary. Instead of focusing on individual candidates, One Michigan printed slate pieces that were organized by state Senate districts and presented Democratic candidates up and down the ballot as a unified team. After aggressive candidate recruiting, they made sure not to abandon them to local partisanship, as is so often the case in state politics.

Demoxrats launched the One Michigan coordinated campaign in June and wound up with nearly 100 organizers on the ground in addition to the countless volunteers that criss-crossed their districts. Unions and other supportive organizations would also knock on what would ultimately be three million doors by Election Day.

The primary for governor was a heated one, with Sen. Bernie Sanders endorsing a young leftist public health official named Abdul El-Sayed against former state Senate Minority Leader, Gretchen Whitmer, who was somewhat more moderate and close to the party apparatus. Whitmer wound up winning by 22%, but the ticket was rounded out by a progressive candidate for attorney general in Dana Nessel and a voting rights warrior in Jocelyn Benson running for secretary of state. El-Sayed immediately endorsed Whitmer, which helped to avoid acrimony.

The ticket promised to “fix the damn roads,” as Whitmer’s campaign put it, while also investing in education and safeguarding Obamacare and abortion rights.

A blue wave swept most states in 2018, but it was especially pronounced in Michigan. The newfound energy and comprehensive candidate recruiting both played a significant role that fall, as did a series of statewide ballot initiatives that Democrats sponsored and proactively promoted. Marijuana legalization proved especially popular, as did an amendment to create an independent redistricting commission that would draw up fair legislative and Congressional districts after the 2020 election.

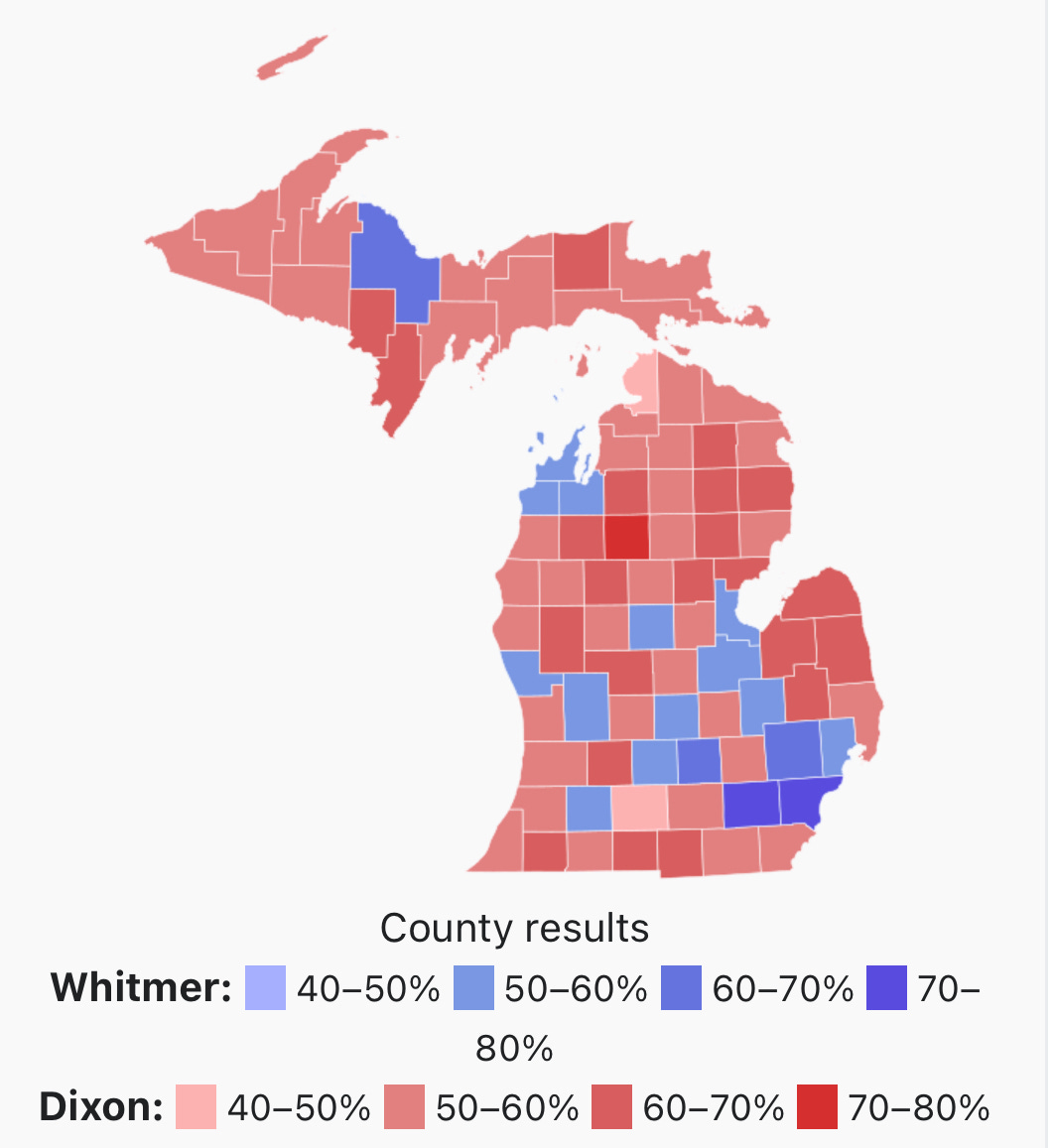

Whitmer crushed her opponent, GOP Attorney General Bill Schuette, by 10% as Democrats also flipped five seats in each house of the legislature. The legal weed initiative won by more than 11%. The independent redistricting commission proposal passed by a massive 23%. A series of policies aimed at expanding the right to vote, including same-day registration, were codified with the support of a full two-thirds of Michiganders.

Democrats were still in a deep rut in the state legislature due to GOP gerrymandering, but those latter two initiatives would soon prove key to changing the situation.

The demographic and geographic advances were also important prelude to future successes. Whitmer made serious inroads in traditionally red exurban regions such as Grand Traverse County and Ottawa County, the most conservative in the state. Democrats also began finally flipping the wealthy suburban areas that produced moderates such as George Romney. Manoogian flipped a historically red seat in Oakland County, a suburb of Detroit where locals were repulsed by Trump’s first two years in office.

“I ran in a district that was gerrymandered to be solid Republican, with a country club Republican base,” she explains. “It very clearly was a shift away from the Republicans as the Republicans trended more towards populism and a fervent white nationalism. I’m the daughter of a labor organizer, but I’m also somewhat moderate for my party today.”

Manoogian flipped her district by 20 points even before it could be redrawn to be more competitive.

First Term in Power

Republicans in the legislature stripped Whitmer of some of her powers during the lame duck session after the 2018 election, which set the stage for the next few years of combat. Partisan gridlock in 2019 gave way to the sort of societal discord fostered by the Covid pandemic and conservative firebrands.

Whitmer was severely underwater after her first year in office, with a lowly 33% approval rating at the beginning of 2020. Then the pandemic hit, exposing the depth of the fissure that ran through the state’s politics. As with many states with split governments, pandemic precautions became a focal point of tension and legal action.

The three women at the top of the state government had to put on a united front, especially as right-wing militias began to stir across Michigan in response to Gov. Whitmer’s pandemic policies. Emergency orders were extended, drawing the ire of the GOP legislature and fringe protestors in front of the Capitol, especially after she gave the response to Donald Trump’s State of the Union address. The president, as if he had nothing better to do as the country buckled under mysterious new virus, began regularly attacking her on Twitter, which summoned the hounds.

“Dana Nessel was making sure the Covid orders were legal, while Jocelyn Benson was being protested at her house at the same time that Whitmer was getting all of her hate,” Demas says. “So I think there is a very deep solidarity and not any infighting, really cutting against the traditional narrative of women in politics, which I have to say is extremely refreshing. It’s helpful when you have a team that works together.”

By the fall of 2020, nearly 60% of registered voters in Michigan approved of her response to Covid, bringing her approval rating well over 50%. The people that disapproved of her policies were not interested in public persuasion.

Armed protestors entered the state Capitol building in Lansing in early April, and at least 13 of them, part of a delusional cosplay army with the embarrassing monicker the Wolverine Watchmen, were involved in an attempt to kidnap Whitmer that was revealed weeks before the election.

Joe Biden would go on to win Michigan by 3.5%, the largest margin for any Midwestern state. His victory, predicated on his own promises to revive the automotive industry, caused even more right-wing believers to lose their minds, which would prove decisive in the next election, two years later.

A Fair-ish Fight

Republicans saw the writing on the wall: An independent redistricting commission threatened their gerrymander, and with it, their ongoing control of the state legislature. There were bills introduced to repeal the amendment, stymied funding, and some speedbumps and lawsuits, but when the commission completed its work, Michigan had new maps that were no longer manipulated by Republicans.

The new districts weren’t exactly friendly to Democrats, as they still maintained a conservative tint — at least according to how the state voted during the 2020 presidential election. They also upset Black communities, who sued over the lines watering down their influence and power. But all-in-all, they were a vast improvement, and gave Democrats a chance to take control of the entire state, should they improve their margins in red areas.

That is exactly what happened, for a number of reasons.

First and foremost, the GOP candidates were totally unhinged.

At the top of the ticket was a former talk radio host named Tudor Dixon, a far-right Trump acolyte who won the nomination almost by default after a signature gathering scandal disqualified much of the rest of the field. After playing to the base to win that nomination, she had trouble pivoting to the center, in part due to the years of insane comments she made on the radio and despicable allies.

Funded by the DeVos family, Dixon went hard after public schools, touting a program that would have robbed public schools of $50 million every year to fund private schools. Whitmer vetoed the program after the legislature pushed it through, and it became a focal point in some elections across the state.

“The kinds of things that we were talking about were very much kitchen table, pocketbook issues,” says Manoogian, who chose not to run for re-election but was involved in this year’s campaigning. “Issues like investing more in our public education system and attracting talent to our state by making sure that our healthcare and abortion-related laws weren't driving people away. Things that really matter a lot to the vast majority of people.”

The party would go on to increase margins in Manoogian’s Oakland County altogether, cementing — for now — that moderate electorate as solid Democrats. Whitmer opened an Office of Rural Development at the beginning of 2022, which helped to cut into deficits in those counties for Democrats.

Whitmer had a modest record, due to partisan gridlock and that pesky virus taking up most of her time, but her Covid policies remained relatively popular, enough so that any backlash was restricted to the backwaters of weirdos who try to kidnap governors. Democrats seized on that far-right energy, contrasting their strong recruits for both Congress and the state house with GOP lunatics.

“They were able to successfully make the case that a lot of Republicans they were running against had been election-deniers and were on record saying they supported abortion with no exceptions,” Demas explains.

Abortion was also key. Even before the Dobbs decision, Whitmer, sensing that the end was nigh, sued to block a 1931 law that would have triggered an abortion ban in the state once Roe was overturned. A legal fight ensued, and in the meantime, activists rushed to get an amendment on the ballot to codify abortion rights in the state.

Proposal 3 passed with flying colors, taking 57% of a record-setting overall vote total. Both of those numbers were assisted by the rush of newly registered voters enabled by the 2018 voting rights amendment that allowed for same-day registration. That proved elemental to huge turnout among young people, who gave Democrats their greatest margin with a single demographic.

At the University of Michigan, students were lined up for hours, waiting to vote. Chris Savage, the Chair of the Washtenaw County Democratic Party, says he got the call to help support college students waiting to register and vote at the University of Michigan’s main campus in Ann Arbor late into the evening. The cavalry soon arrived with pizzas, blankets, and other survival essentials.

“The last person to vote was at 2:10 am,” he tells Progress Report.

Thanks to a successful ballot initiative that will expand early voting, they’ll able to avoid the lines in 2024. With an agenda that insiders say should include repealing the state’s “right-to-work” law, codifying protections for LGBTQ+ people, investing heavily in public education, and continuing the reintroduction of unionized industry to the state, it’s now up to Democrats to deliver.

Wait, Before You Leave!

Progress Report has raised over $7 million dollars for progressive candidates and causes, breaks national stories about corrupt politicians, delivers incisive analysis, and continues to grow its paid reporting team. Yes, we pay everyone.

None of the money we’ve raised for candidates and causes goes to producing this newsletter or all of the related projects we put out. In fact, it costs me money to do this. So to make this sustainable, hire new writers, and expand, I need your help.

For just $5 a month, you can buy a premium subscription that includes:

Premium member-only newsletters with original reporting

Exclusive access to group chats

Financing new projects and paying new reporters

You can also make a one-time donation to Progress Report’s GoFundMe campaign — doing so will earn you a shout-out in an upcoming edition of the big newsletter!

Fun & honest bits of news.