How to overcome the Democratic disconnect (Part 1)

Welcome to a Monday evening edition of Progress Report.

Based on the final top line numbers and election night maps coded in blue and red, Democrats enjoyed an improbable success this year. They defended their Senate majority, flipped several governorships and state legislatures, and minimized their losses in Congress. But dig a little deeper and you’ll see that a few thousand votes flipped in a few different places could have turned what was a resounding success into a serious disaster.

It requires far more than just good luck to beat the odds in a hostile midterm cycle, but Democrats did get a fair amount of luck this year, mostly in the form of a Republican lineup of historically dopey and dangerous candidates. Had it not been Kari Lake running for governor in Arizona, Hershel Walker running for Senate in Georgia (fingers crossed), or that guy who faked his military record running for the House in Ohio, things may not have been so unexpectedly sunny for Democrats on November 9th.

It’s neither practical nor smart to rely on Republicans to continue nominating whacked out candidates in perpetuity — they’ll learn to stop or find way to install them — so it’s essential for Democrats to seize on this reprieve from doom and formulate a long-term game plan for both how to approach politics and use power.

Tonight’s newsletter is the first part in a series that will lay out how Democrats can become a party that competes everywhere in the United States and deliver on the many promises that they have yet to fulfill.

Thank you to our latest crowd-funding donors: Harold, Suzanne, Patti, Stephen, Marvin, Gerald, Susan, Ann, Ione, Charlotte, Kevin, Raphael

The Big Disconnect

When voters in Kansas overwhelmingly rejected the state’s anti-abortion ballot initiative in August, it gave Democrats hope that they could ride a wave of pro-choice, anti-extremist backlash to a rare midterm elections victory for the party in power.

To some degree, that’s exactly what happened. Instead of coughing up recently flipped territory, as is so often the case, Democrats defied the odds and won nearly every statewide election in the states that Joe Biden won in 2020.

In red states, the dynamic instead turned out to be a lot like the dynamics of the prior three elections: Voters embraced progressive policies via ballot initiatives, but rejected the party that supported those policies in favor of the party that was openly hostile to them.

In effect, the same partisan lines became further entrenched, underscoring the tribal nature of our politics.

So why did voters in these states gravitate toward traditionally Democratic policies while expressly rejecting Democrats themselves? Both are expressions of self-interest: They got to vote to secure some specific material benefit while still thumbing their nose at a party that they either think has lost touch with their concerns or is secretly a gang of devil-worshipping, Caucasian-hating pedophiles.

It’s happened all over the country, including ruby red states such as South Dakota, where voters approved Medicaid expansion at the same time that they renewed the Republican trifecta.

Given the state’s longtime conservative lean, it’s probably not the best example of the disconnect. Instead, let’s look at Missouri, a former swing state that has become solid Republican in recent years while at the same time embracing one progressive policy after another via ballot initiative.

In 2016, when Missourians were backing Donald Trump by nearly 20 points, they also voted to enact serious limits on campaign contributions. In 2018, they held out against the blue wave yet voted for medical marijuana and a raise to the minimum wage, while also soundly rejecting a proposed “right to work” law that would have eviscerated unions. Last cycle, Missourians gave Trump a 15-point victory after voting to approve Medicaid expansion a few months earlier.

The same pattern held this year: Missouri voters gave the green light to legalizing recreational marijuana at the same time that they handed Republicans a statewide sweep.

The incongruity is somewhat astonishing: In a major poll of Missourians conducted in late August, voters there indicated that they opposed the overturning of Roe v. Wade, wanted to see fewer restrictions on abortion, favored more gun control, and thought that the state should do more to help the poor. At the same time, they registered a 63% approval rating for the GOP-controlled legislature, which has very publicly opposed and blocked those things.

There’s no one single problem causing this disconnect. It is instead a systemic problem, the result of individual mistakes, institutional rot, and an inability to keep up with the times.

Winning and losing are both the product of the stories we tell, the tangible results we deliver, and the long-term structures that we create.

The Stories We Tell

He said it nearly a century ago, but Will Rogers’s famous quip from 1928 rings true once again: “I don't belong to any organized political party. I'm a Democrat.”

Four years later, Franklin Roosevelt ascended to the presidency and cemented the Democratic Party as the home of working people for the next 50 years, but that identity has long since faded. Over the past five decades, the Democratic Party has again become a coalition with vaguely similar interests and goals, all of which are ultimately subsumed by an allegiance to business interests protected by politicians who share little in common with its base.

This year, Democrats’ lack of coherent identity contributed to Republicans’ winning the popular Congressional vote this year, even while running some of the worst people alive. And for all the high-profile losses taken by Republican election-deniers, there was still a crop of absolutely batshit GOP candidates that won their elections. In some places, they were the only real options on the ballot, but in others, a more normal option was doomed by the (D) next to their name.

Republicans have been able to brand Democrats as a bunch of police-hating communists in part because it fills in a vacuum left by Democrats’ failure to create a viable identity of their own. The media echo chamber helps perpetuate that perception, and we’ll talk about that in the next part of this series, but there are many other reasons for that struggle, as well. First and foremost of which is a persistent credibility gap.

“The number one question that we lose rural voters on is ‘Are Democrats fighting for you?’” Matt Hildreth, a long-time Democratic organizer and the executive director of RuralOrganizing.org, tells Progress Report. “Rural voters overwhelmingly support Democratic policies, and even on the most ‘wedge’ issues like abortion and banning assault rifles, 50% of rural voters are with Democrats.”

Unfortunately, elections will never be wonky debates about specific policies, but instead about two much more fundamental questions. The first is the one that Hildreth posed, which is more of a gut-check than sober analysis of a politician’s voting record. As such, the first thing that Democrats must do, Hildreth suggests, is focus on candidate quality.

Take Pennsylvania Lt. Governor John Fetterman, who wound up winning a bitter, neck-and-neck Senate election by nearly five points last month. In hindsight, he was a slam dunk, obvious candidate for a swing state with a high percentage of blue collar, working-class voters in rural and post-industrial towns. Pull the lever on a candidate slot machine and the jackpot for Pennsylvania would look a lot like a giant bald guy with tattoos, an advanced Ivy League degree, and a disdain for formalwear who flew a marijuana leaf flag from the balcony of his office in the state Capitol.

But Fetterman was not the candidate that the Democratic establishment — and crucially, the financial interests that fund so many Democratic campaigns — were hoping to nominate. Instead, they were dead-set on ensuring that the ballot line went to Rep. Connor Lamb, a bland centrist whose first act in as a member of Congress was to vote with Republicans on a banking deregulation bill. Both candidates grew up in well-to-do households, but only one of them had spent decades living and working in working-class neighborhoods.

“There's a real perception that Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi are picking candidates from New York and San Francisco,” Hildreth says. “Republicans have spent a ton of money saying ‘Democrats don't live here, they’re not from here, they’re from these other places, and they're reaching into our communities and pulling puppet strings.’”

It’s not an entirely untrue statement, either. Lamb’s Senate campaign was bankrolled by financial interests and backed by PACs and most elected officials. But that institutional support couldn’t overcome Fetterman’s monster grassroots fundraising hauls, which were in turn derived from a public persona that was playful yet antagonistic about him.

Even while Fetterman was waylaid from public appearances while recovering from a stroke, the snarky tweets about Dr. Oz’s home in New Jersey and his weird grocery store habits generated a unique excitement that translated to broader appeal and more money. In the general elections, Fetterman significantly improved on Biden’s numbers in rural areas without sacrificing the cities and suburbs.

Lamb, on the other hand, ran on an archaic notion of electability that has nothing to do with the contours of today’s politics.

Given that the party was up until last week still entirely run by politicians whose formative political experiences took place during the Reagan Revolution, it’s not surprising that its standard definition of “electable” continues to be socially liberal, fiscally conservative, and agreeable to a polished suburban middle class. (It probably doesn’t hurt that there significant financial incentives to keep it from straying from the neoliberal ideal.)

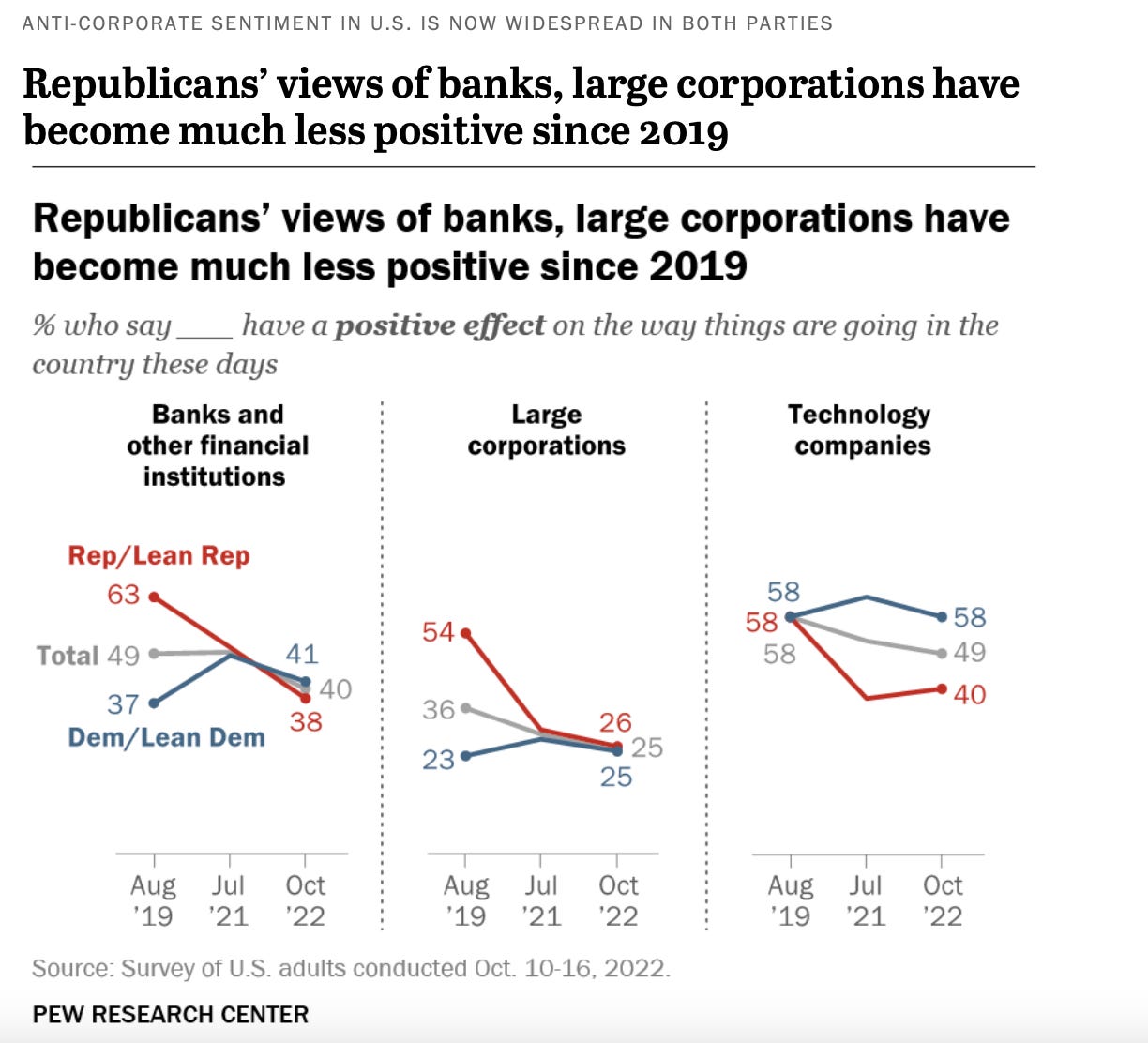

In reality, though, income inequality, a 15-year housing crisis, and now inflation have turned Americans into free market skeptics like never before.

Not every candidate has Fetterman’s qualities — aesthetically, he’s one of a kind — so Hildreth recommends empowering local leaders that have proven to have the tenaciousness required to function in hostile political environments.

“Some of the most influential people in our network are progressives who lost their primary because they weren't seen as the electable candidate,” he says. “But if you look at the votes that they were getting, their dollar-per-vote in the primary was just way, way, way less than the candidate that went on to win it.”

There’s no better example of that than what happened in this year’s Missouri Senate primary. Military vet and antitrust activist Lucas Kunce was beginning to build up momentum in a populist, insurgent campaign built on grassroots donations and anti-corporate fervor, at least until the late entry of self-funding beer heiress Trudy Busch Valentine.

Powerful Democrats in the state lined up behind Busch Valentine’s campaign, which didn’t even bother to feign any insurgent spirit. The night she won the primary — by just five points, despite all the financial and establishment advantages — Busch Valentine might as well have delivered a concession speech.

In November, she did exactly that, having been obliterated in the general election by the state’s charmless attorney general.

Ohio Democrat Tim Ryan’s Senate campaign provides another kind of cautionary tale. He ran as blue collar pugilist, unapologetic about his willingness to fight for the Rust Belt laborers. A long-time creature of Washington, he tapped the anger he felt from workers in his hometown of Youngstown, including darker elements of white resentment.

Ryan’s rhetoric battered China to the point that it sometimes veered from criticisms of unfair global trade to downright bigotry, at a time when anti-Asian hate crimes continue to proliferate. He also raged against the “elites” of the Democratic Party itself, blaming it for failing to stop the decline of Midwestern manufacturing and catering to special identity interest groups, including going hard after student debt cancelation.

While not wrong about Democrats’ history of failure on trade, his regular attacks on the party and its base took on a bitter tone. The end result was a bump in working class white support that was negated by a depressed turnout in Ohio’s largest counties, which regularly provide Democrats with their biggest margins.

“A lot of Democrats, when you hear them talk, it's this self-hating thing, like ‘there's something wrong with us and real people don't like us,’” Hildreth says. "It has to be both/and strategy: You have to be able to persuade people who aren’t with us when it comes to party ID but are with us on policy, and then also you need to be able to mobilize the base.”

Following an underwhelming 2020 election, Democrats at the highest levels spent two years rebuking the Black Lives Matter movement and turning the slogan “Defund the Police” into a straw man that conservatives torched over and over again. Virginia Rep. Abigail Spanberger’s relentless media blitz decrying BLM helped to set the table for Glenn Youngkin’s racist campaign for governor the next year.

The Results We Deliver

The best way to successfully execute Hildreth’s both/and strategy is to improve people’s lives through government.

For Democrats, campaigning has generally meant touting a regime of economic populism, while governing has been a practice in failing to deliver on those big promises. If the party wants to excite its base, solidify its advantage with swing voters, and at least make inroads with working class people outside of urban areas, producing material benefits for people must also become a more pressing priority.

The expanded Child Tax Credit lifted millions of children out of poverty, many of whom were plunged back into extreme hardship upon the credit’s expiration. The subsequent failure of Build Back Better’s social spending proposals meant that Democrats in Congress did not produce a single new immediate material benefit for working Americans in 2022.

(You can protest by citing the Inflation Reduction Act, infrastructure law, and CHIPS package, but when people are worried about paying next month’s rent, they’re simply not going to care that some company will at some point down the line be getting money to fix highways or build computer hardware factories. Long-term planning is a luxury in a country where most people don’t have enough cash to cover the bill for a sudden trip to the emergency room.)

There is little chance of some major progressive policy passing while Republicans control the House, but the next few years can be spent mainstreaming ambitious ideas for unaddressed issues; using existing funds to deliver grants that can circumvent Republican governors eager to dump money into school vouchers and private prisons; and using the enhanced regulatory state to crack down on bad corporate actors.

At the state and local level, an increase in blue trifectas and Democratic governors should also provide the opportunity to deliver significant wins for middle- and working-class people.

New trifectas in Minnesota and Michigan especially will be under pressure from labor to deliver victories on education, workers’ rights, and housing in quick succession, while New York Gov. Kathy Hochul is already facing a growing drumbeat to shift away from solely serving real estate developers after a dismal November for Democrats — first up in January, a bill to raise the stagnating state minimum wage.

In Colorado, affordable housing shortages will continue to demand attention from lawmakers. In midwestern states that have Democratic governors, such as Kansas and Wisconsin, the development of strong rural economic development policy that contributes to the revival of manufacturing and other local industries will be pivotal, too.

Good policy is good politics, especially when the outcomes are unambiguously positive. It can drown out the lies and keep all the contrived distractions from adding up to something bigger.

In New York, Hochul’s failure to deliver for anybody other than the billionaire owner of the Buffalo Bills left people to stew over immense housing costs and misleading crime blotters. The fallout cost Democrats four seats in Congress, which in turn just about cost them the majority.

The New York state party is in desperate need of new leadership that can root out corruption and breathe new life into moribund county parties, which is something that can be said for most states.

There will be much on that, as well the challenges and opportunities posed by media, outside allies, and shifting cultural dynamics, in the second half of this examination.

Wait, Before You Leave!

Progress Report has raised over $7 million dollars for progressive candidates and causes, breaks national stories about corrupt politicians, delivers incisive analysis, and continues to grow its paid reporting team. Yes, we pay everyone.

None of the money we’ve raised for candidates and causes goes to producing this newsletter or all of the related projects we put out. In fact, it costs me money to do this. So to make this sustainable, hire new writers, and expand, I need your help.

For just $5 a month, you can buy a premium subscription that includes:

Premium member-only newsletters with original reporting

Exclusive access to chat

Financing new projects and paying new reporters

You can also make a one-time donation to Progress Report’s GoFundMe campaign — doing so will earn you a shout-out in an upcoming edition of the big newsletter!

This one really grabbed my attention. Dovetails also with the need for the Dem Party to invest in voters year in and year out - with their governing power and with their voter outreach and engagement. It's my sense that it's all the progressive grassroots roots that are responsible for as much progressive progress as we got this year.

I agree with you, Democrats really need to stop catering to neoliberal interests in order for them to be “electable” and have to connect with people in rural areas and make a real difference in their lives. That’s the path to power for Democrats up and down the country.